The Outsider Option: Why I Sold Half my Company to Tiny

I had the most curious sensation when I was working the other night: I was kind of happy.

You know, not just in the I find this work satisfying kind of way, but in the and I don’t also want to walk out a window kind of way. This latter is, in my professional life at least, something of a novel experience.

It is often said that founding a business is like “staring into the abyss and eating glass.” I concur with this analysis.

But I would go one further. As someone with a chronic serial entrepreneurship problem, I can vouch that the life of a founder is actually also often quite painfully lonely—a feeling that somehow, paradoxically, gets worse the more employees and clients one has.

'Twas ever thus, I used to think, and ever would be. It all just seemed like part of the entrepreneurial bargain, the cost of creative freedom. It’s a price I myself have been willing to pay at times, but at other times not so much.

Just over a year ago, in fact, I very nearly shuttered my latest business, Norbauer & Co. (We make very fancy luxury computer keyboards—yes, that is a thing; I’ll explain.) It wasn’t that we had any actual problems. Quite the contrary. We were enjoying a commercial success far exceeding anything I had ever hoped for or intended. It was just that this success required so very frequently dining on glass, as I bounced from one annoying-but-important logistical challenge to another.

But let’s advance one year forward, to just last week. I found myself at the end of a long day grappling with a hard operational problem for the company (which indeed I did not shutter). It’s the sort of manufacturing setback that would previously have sent me down a vortex of despair, as I felt the latest shards shattering between my teeth. Yet in that moment the other night as I was wrapping up my work I caught myself smiling like an idiot, oddly untroubled.

(Sometimes we get these rare glimmers of insight in life, when we briefly stumble off the hedonic treadmill. The perspective zooms outward, and we perceive that our past selves would be astonished and delighted by our situation in the present. It’s a beautiful thing.)

I now have at my disposal an executive team of a caliber and competence I would never previously have thought within my grasp, leaving me never facing a problem alone. We have, moreover, just launched a product of enormous ambition and complexity that has been a lifelong creative dream of mine. Until these facts suddenly occurred to me at once the other night, they had somehow crept up on me over the past year without my quite noticing.

I very intentionally capitalized and bootstrapped Norbauer & Co. in such a way as to never need outside investors, and at no point (now or in the past) have we ever been in want of cash. Indeed, I have spent my entire entrepreneurial life resisting investor-oriented management. So, as I now find myself more tranquil and satisfied than I have ever been in all my working life, I’m reluctant to admit what made it all possible.

I sold nearly half of my company to a publicly-traded investment fund run by a Canadian billionaire.

History of a Great Deal, and a Great Deal of History

This is the story of my accidental luxury brand and our eventual deal with the very unusual investment firm Tiny.

I tell it in detail here not only for keyboard enthusiasts who may care about the past and future of Norbauer & Co. (or fans of Tiny who may wish to peer behind the curtain of one of their deals) but for any entrepreneur who struggles with the desire to bring a singular creative vision into the world—and who worries, quite rightly, about the perils of working with investors to make it happen.

Tiny counts in its portfolio well-known cool-kid brands like Aeropress, Letterboxd, Dribbble, Serato (note: I added this last newly-announced one as an update after publishing this post), and more than a hundred others—many of them design-centric businesses that, like mine, are deeply rooted in communities of passionate nerd enthusiasm. They also own quite a few creative agencies (such as Metalab and Frosty), which do tasteful projects for luxury and luxury-adjacent brands such as Prada, Apple, Burberry, Calvin Klein, and many others. This all makes Tiny an improbably good spiritual fit for my company, but my reasons for the deal actually ran far deeper.

Many founders, especially those in the VC sphere, tend to view outside investment as a path to an “exit” payday, allowing them to cash out and ride off into a tropical sunset. Tiny has, to be sure, facilitated numerous embarkations of this type. But in my case, the short-term financial aspects of the sale were, for both sides, actually something of an afterthought. Far from exiting anything, I continue to serve as CEO of Norbauer & Co., and, as majority voting shareholder, I retain absolute control—creative and otherwise—over the business.

Even though we closed the deal a year ago, I intentionally waited until now to write about it publicly, because I wanted to proceed from actual experience rather than the blind fact-free optimism of an early-day press release. The result, happily, turns out to be something of a love letter to a very unusual investment fund and the singular philosophy (and integrity) of the people behind it.

A Keyboard Snowball

In an article published a few weeks ago, Hodinkee (a magazine quite influential in the luxury world) described Norbauer & Co. as the brand “defining the world of high-end analog keyboards,” which is very kind, and perhaps even true in a way, but is mainly just amusing to me given how much I dragged my feet in letting it even become a business in the first place—to say nothing of an industry-defining one.

Norbauer & Co. is in fact an entirely adventitious business and the unintended byproduct of an aborted attempt on my part at retirement. In 2010, having sold the last of three tech companies I had founded, I resolved to take a little breather from crippling stress and life-destroying workaholism to throw myself instead into frivolous, low-stakes creative pursuits. The effects were so salutary that I quickly swore off ever starting a company ever again. But among those fun creative projects was one that would end up quickly undoing my resolve: figuring out how to make my own retro keyboards.

On obscure forums like GeekHack, I began organizing group buys for my designs among fellow hobbyist enthusiasts. These offerings were originally intended just as a way to help offset the cost of making a few units for myself. From my very first such sale almost a decade ago I kept swearing that it would also be the last, intent on keeping my resolution never to get sucked into running another business and letting the stress ruin my life again. And yet I found myself nudged along at every turn (albeit gently and kindly) by an eager crowd with whom my work seemed to be resonating. One offering led to another. And things just sort of snowballed from there.

The Norbauer brand has since managed to accumulate a base of thoughtful and loyal clients all around the world (from South Korea to the UAE, South Africa to Mongolia), and I’ve somehow never quite been able to keep up with demand. Most of our offerings sell out within hours—sometimes minutes—of being posted. (Communities of collectors have even set up bots to track our inventory and broadcast availability to private channels on Discord.) For waitlist items, we have clients who preorder and patiently wait for models with production lead times sometimes exceeding a year—including bespoke orders running into the tens of thousands of dollars.

At some point or another, with millions of dollars of keyboards sold—and without my quite meaning or realizing—it had turned into a real business.

Retro-techno-futurism, and a Rationally Irrational Trade

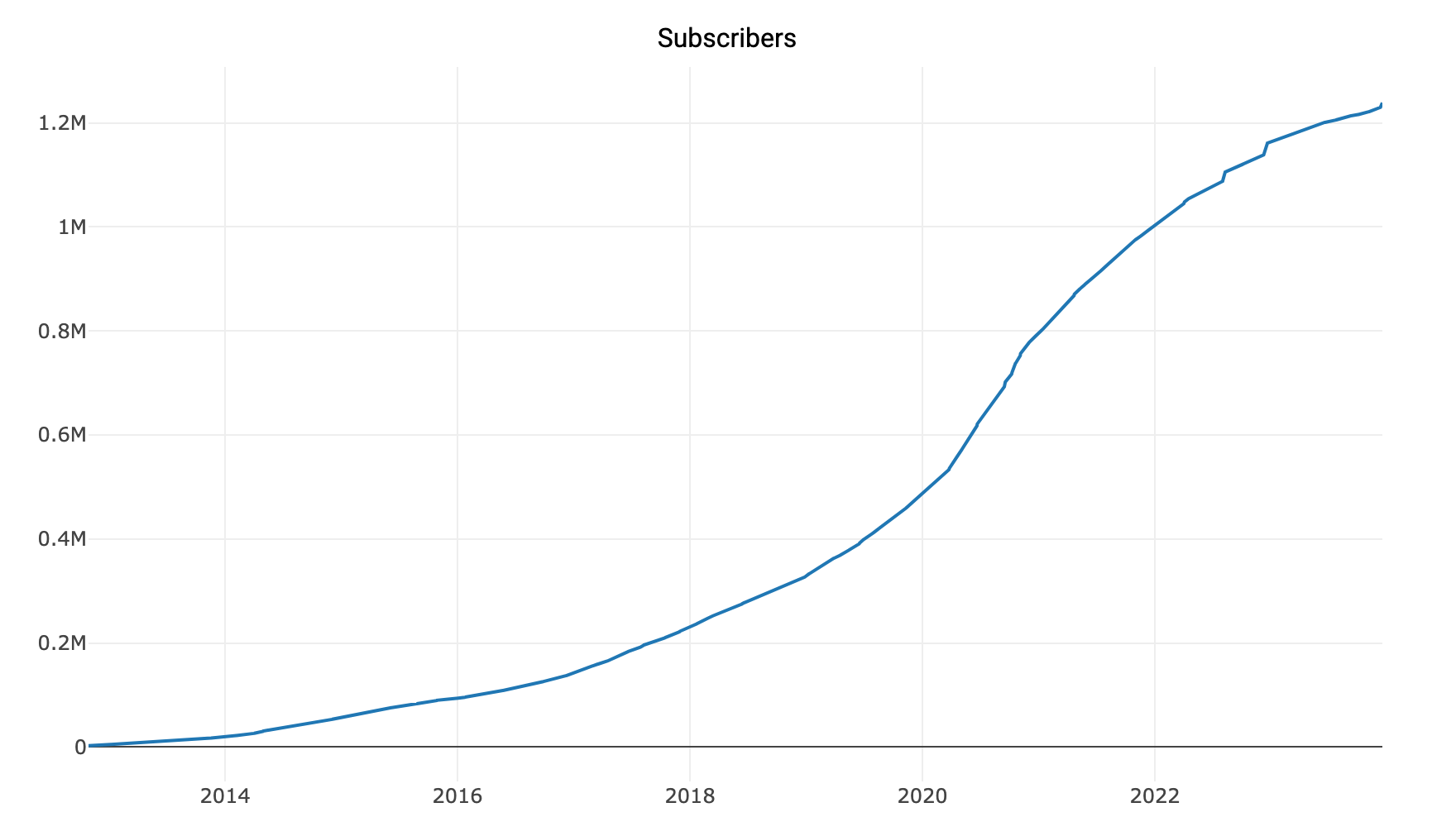

While I have been obsessed with keyboards my whole life, I chose a serendipitous moment (around 2014) to become interested in actually making them. Here is subscribership of the MechanicalKeyboards subreddit over the past decade:

Plenty of other enthusiast-led keyboard brands sprang up at the beginning of this upward curve along with Norbauer. But the vast majority, including some of the most prominent and prestigious ones, have since either spectacularly imploded or faded into the internet mists.

If any one thing has allowed us to enjoy a relative longevity, I believe it’s that our products are fundamentally sentimental—and thus slightly irrational. When other makers seemed to be climbing over each other to be the Lexus of keyboards (converging on a single technical paradigm and competing on checklists of “premium” features), I was far off in one isolated corner, making weird Ferraris.

The thing with a Ferrari—as, like, a car—is that it really isn’t the most logical purchase. They’re loud, difficult to maintain, and not particularly comfortable. I’m happy to report that our keyboards don’t have those shortcomings, but my point is that the unique (and obviously very potent) thing a Ferrari offers is to be an object with a soul—the product of a very specific worldview and set of values. This makes it non-comparable and thus somewhat resistant to direct competition. (Despite, for example, a vibrant market of counterfeit Norbauer keyboards coming out of China—some of which even brazenly copy our packaging—clients still eagerly prefer to pay a multiple to get the genuine articles from us.)

What is it, then, that gives Norbauer products their particular soul? It comes from a profound emotional attachment to the spirit of 20th century techno-optimism. Part of this is our retrofuturist design language, which explicitly evokes midcentury and 80s modernism. Another is the deep and clacky/thocky sound profile, which is intentionally redolent of keyboards from the 80s and 90s. But above all is a headlong dive into the sort of breathless over-the-top optimism that characterized that earlier era of computing—when everyone seemed to believe that personal computers and the Internet were going to break down international barriers and make for a wiser and more peaceful world. A time when we all believed in The Future, with a capital F.

Computers were held to be objects of enormous promise back then—rarer and more valuable devices than they now are—so manufacturers were willing to invest far more into hardware that was both durable and satisfying to use. Norbauer & Co. simply pretends that the trend never stopped—taking finishes, materials, and engineering to extremes to build objects that feel at once worthy and symbolic of those hopes.

But by the mid-2010s when I started making keyboards, the hopes that had been a part of cyber-culture in its early days (decentralization, anonymity, lack of concern with social status or authority, peaceful mutual understanding across cultures, free speech) were already fading away. The charmingly anarchic early Internet was being supplanted by various walled social-media gardens controlled by a few megacorporations, with ill effects that are by now all too familiar—and are largely the opposite of all those things we had hoped.

I think it’s not a coincidence, then, that the upsurge of cultural interest in vintage-style keyboards happened right around this time. For those of us who came of age during the golden era of personal computing (or those who wish they did), vintage-style mechanical keyboards are a small act of defiance—a way to physically reconnect with a time when technology seemed to offer a tomorrow that would always be better than today.

At some point I realized that this meant I was essentially building a luxury brand: one whose value proposition is emotional valence, technical perfectionism, artistic design, and artisanal knowhow rather than serving any obvious practical necessity. (Contrary to popular conception, I believe that a true luxury brand isn’t about monetizing social status but rather enabling low-volume manufacturing of weird and creatively interesting goods.)

I admire many examples in this space—Leica, Teenage Engineering, Hermès—that flagrantly disregard economies of scale, mass appeal, and micro-efficiencies in favor of a quirky creative vision, sold to a tasteful and passionate few who are simply very excited about and believe in what the creators are doing.

I knew that if I were going to continue operating a consumer electronics company, this would be the only kind that I would find interesting to build.

The Withering Gaze of Uncle Scrooge

By 2021 we had opened a workshop in Downtown Los Angeles and I had hired a small team. We had just launched our most popular product, the Heavy Grail (shown in the video below), and our revenue was on an insane parabolic year-over-year upward trajectory.

This was all quite gratifying in a way, but the feelings of avoidant stress from my early entrepreneurial days started to come back. I just wanted to focus on giving our clients what they wanted, doing it well, and making functional art that facilitated a bit of happy escapism. But with increasing success came a whole host of unwelcome burdens and concerns that I was disinclined to manage optimally. Shards of glass again.

I keep a statue of Scrooge McDuck next to my desk as a reminder that making money is something a person running a business should endeavor to do. (Milton Friedman and Jack Donaghy action figures were unavailable.) It is a general entrepreneurial failing of mine that profit is not always foremost in my mind, but this has been more true for me in this “fun little retirement project” than with any other preceding venture.

Having so many people throwing money at us made it easy to do what I was naturally inclined to do anyway: to focus on the product and client experience above all else, while avoiding hard decisions about capital allocation. (More money, more Parkinson’s Law problems.)

Part of the premise and competitive advantage of a luxury brand like ours is being willing to spend way more money on quality and subjective artistic matters than a rational manager would seemingly ever do. But, critically, these expenditures should be focused only on things that affect the client experience. Through my general avoidance of the subject, our profligacy was often directed, utterly un-strategically, by random chaos instead.

By the end of 2023, to cite one example, I had unwittingly flushed a quarter of a million dollars down the toilet in a self-imposed boondoggle project to rework our e-commerce infrastructure. It was a frog-boiling situation; the development team kept assuring me something shippable was just around the corner—probably actually believing this themselves—until I eventually paid some close attention, dug into the details, and realized (years in) that no such thing was forthcoming and had simply to kill the project.

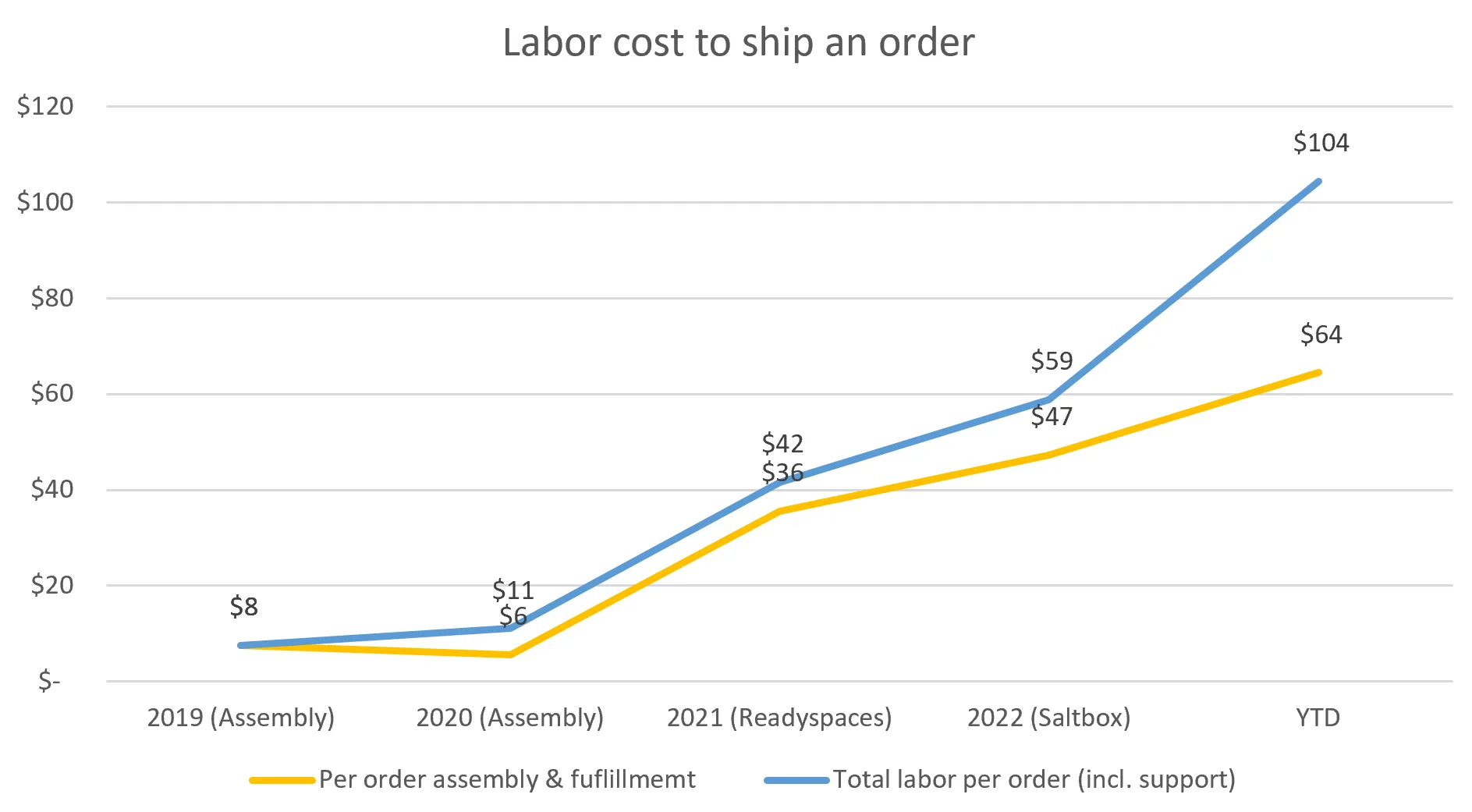

Around the same time, I had a suspicion that our warehouse and client support operations had become wildly inefficient, so I decided to take a look at what it was costing us (in labor alone) to ship an order. I discovered that we had gone from $8 per order in 2019 to $104 per order in 2023, an order of magnitude jump in costs with no appreciable improvement in the client experience.

These were just two rare examples where I diverted my attention briefly away from what felt like my most important responsibilities (design, engineering, and brand), and I immediately stumbled into raging cash incinerators. There was reason to believe that others were lurking around every corner. This was manifestly unsustainable, and I knew it would eventually start threatening our ability to allocate capital to important things that actually did matter to our clients.

There are a million little trivial but non-optional tasks in running a physical goods business: complicated bookkeeping, logistics coordination, inventory tracking and valuation, customs clearances, regulatory compliance, endless tax filings, insurance, payroll processing, accounts payable, etc. Attending to tasks like these tends to drain my will and energy, leaving me with very little enthusiasm for more optional (but no less essential) management tasks like the ones where I discovered us pointlessly hemorrhaging cash.

Spending more time being strategic about management seemed urgent. But I got into this business because I liked making fancy keyboards and connecting with our clients. Diverting my attention even further from those goals seemed horrible to me. This is why, on the day I made those charts and realized all this, I very nearly decided to fold up shop.

The Seneca Moonshot

If it were just a question of going on selling my existing product lines and optimizing the business for short-term profitability, I definitely would have put the company in the garbage right then. What we were making up to that point were essentially “aftermarket upgrades” for keyboard internals made by other companies. Although the community was still clamoring for those products and there was unquestionably money still to be made, I simply felt like I had solved all the interesting design problems in that domain. But I had something else in my back pocket.

I’ve often said that Norbauer products are more than just backward-looking nostalgia. They’re actually meant to feel like they come from an alternate universe that split off from our own in something like the 1980s—an imaginary timeline where technological evolution continued in parallel to ours but where both the sensual quality of computing hardware and its broader social effects just kept getting better and better (rather than, say, what actually happened). This is why my long-term goal has always been not just to recreate vintage-feeling keyboards, but rather to make new keyboards in a retrofuturistic design language that are actually better than any that exist in our real universe, now or in the past.

And so in the preceding years I had been quietly working on a crazy (and crazy expensive) multi-year moonshot project to develop our own in-house ready-to-type keyboard—something that a client who wants the best typing instrument obtainable in the world could acquire from us, plug in, and immediately enjoy. Every component would be custom, right down to the screws. I called this project the Seneca, and by the time I was thinking seriously of shuttering Norbauer & Co., it was actually very near completion.

This put me at a crisis: I didn’t want to go on running the business any longer, but I also didn’t want to give up on the creative vision either; I had become sentimentally attached to the idea of seeing the Seneca out into the world.

This is where a normal entrepreneur would look to outside partners or investment. But I was so profoundly allergic to this prospect that I remained blind to it, probably for far longer than I should have. Then again, for a founder like me—whose priorities are creativity and the client experience—I think the hesitation was quite warranted.

Effing the Ineffable (MBAs Ruin Everything)

There is a natural tension between the pecuniary concerns of the investor and the creative urges of the builder-entrepreneur, and I am certainly temperamentally much more aligned with the latter. But my complaint about investors is not that they’re somehow too obsessed with making money; it’s that—in the long term at least—they’re just generally so bad at it. (And this coming from a guy who has to keep a Ducktales figurine by his desk as a reminder to think about profit occasionally.)

The Swapping of Cerebrum for Spreadsheet

Because the core premise of investing is “sit at computer, make number go up,” it seeks above all else things that can be easily measured and thus optimized.

The folly generally takes one of three forms:

- Venture Capital. For VC firms, the target is meteoric growth, typically in things like size of user base (profit unimportant) in order to hype the share value for the next round of speculators. This can and often does doom innovative companies that would have been great profitable businesses at smaller scales.

- Private Equity. Here it’s the value of underlying assets to be carved up for leverage and/or quick sale to the highest bidder, even if the source of the company’s value generation is itself obliterated in the process.

- Public markets. Here the focus is typically juicing quarterly accounting numbers and massaging narratives for modest ticker jumps at the next earnings call.

There seem to be no good options.

The startup trajectory is typically as follows: a company starts out doing something good, which catches on and becomes profitable. A core community of enthusiastic and happy customers grows up around the brand. Success attracts investment and a concomitant push to scale. Loath to rise from their computers, the investors seek numbers that can be upwardly coaxed on the screen, and their armies of MBAs are deployed to find them. Things that are easy to measure and control like costs and revenue growth get over-optimized, focusing on easy paper-based wins 📈 over the gestalt of the business and its reputation. Quality degrades, and customer loyalty with it. The brand undertakes a slow march toward mediocrity and eventual death, its pricing power ebbing away, all while the MBA managers and consultants (and often the investors themselves) have long since gotten their payouts and moved on.

This is an unseen homogenizing force in the world of commerce, draining every last wisp of human dignity and aesthetic joy from some of the world’s greatest brands and institutions—eventually, and ironically, also destroying their economic value in the process. And it leads to the opposite of the very reason I ever wanted to start companies to begin with, which is to make the world look a little less boring.

MBAs are why we can’t have nice things.

Sure, I may be slow to undertake performance analysis and optimization when running a business, but I’d far rather have that problem than these.

Oops

…many managers attempt to reach their targets simply by cutting costs. This can be fatal. Any fool can cut costs anywhere at any time. For one shining moment it will look as if he or she is a genius at increasing the bottom line. Then the moment will pass … and quality will collapse.

—Felix Dennis, How to Get Rich

Although excessive cost-cutting is among the most common, it’s just one example of the investor-driven impulse to focus on metrics— and how this can insidiously erode the foundations of a business over time.

“When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure,” as Goodhart’s Law states, although that formulation actually puts it a little too modestly. I prefer the Strong Version of Goodhart’s Law, as expressed by machine learning researcher Jascha Sohl-Dickstein: “as you over-optimize, the goal you care about won't just stop improving, but will instead grow much worse than if you had done nothing at all.”

This applies across many domains of human endeavor (standardized testing making students dumber being the most obvious one) but let’s consider a few examples from the world of business.

- Facebook seeks to improve the world by fostering human connection, choosing engagement with the platform as the proxy metric to guide its algorithms; the result is that people’s “social” feeds fill up with attention-grabbing viral content and virtually no posts from actual humans or friends.

- An e-commerce brand seeks to increase cashflow and chooses average order value (AOV) as its proxy metric; managers make offerings like free shipping at certain order total thresholds, causing customers to order things they don’t really want, leading to decreased customer satisfaction and increased returns (with a net negative effect on cashflow relative to baseline).

- A streaming service seeks to optimize customer enjoyment and chooses time spent watching video as its proxy metric; the result is that managers focus resources on building auto-play, infinite scroll, and low-value ambient content that spikes the numbers while actually just pissing customers off.

I could go on. Jerry Muller’s The Tyranny of Metrics is an entire volume dedicated to this phenomenon, as is much of Nassim Taleb’s brilliant Incerto series, a nearly 2,000-page screed against what he rightly calls naïve rationalism and the frequent backfiring of over-reliance on quantitative models and targets.

The Hard-nosed Economics of Emotional Attachment

So, yeah, metric optimization is dumb. But it is even more often the case that the most important things can’t even be measured at all.

Despite much quantitative window-dressing to the contrary, business is actually an inherently social and thus profoundly subjective, psychological, and qualitative phenomenon. The real earning potential of a company emerges not primarily from its book assets but its brand and reputation, for it is only by that reputation that it is able favorably to undertake the transactions that make those assets worth anything. The goods and services of an untrustworthy (or, worse, hated) transaction partner will trade at a significant discount to what they would be from a favored one. As Danny Meyer (founder of Shake Shack) is often quoted, “business, like life, is all about how you make people feel. It’s that simple, and it’s that hard.”

Social and emotional matters are thus of paramount importance in business, yet they cannot meaningfully be quantified, and, as we’ve seen, attempting to use proxy metrics to optimize them can easily have the opposite of the intended effect. Customer enjoyment and loyalty are slippery things. A company must always be obsessively imagining and empathizing with the totality of the customer experience, which is a matter of great nuance and subtlety, hard to characterize and dynamically changing across time and multiple dimensions of interaction. A constant attention to this kind of empathy must be embedded deep in a company’s culture—and no amount of net-promoter-score surveys will do the trick.

The Founder’s No (Protecting the Extraneous Essential)

We only want to make great products and when you don’t focus only on making money and have reached a certain level, everything becomes about quality. Right now, there is a certain cultural fascination with fast growth, IPOs and so on, but I want to go slow, really slow and think long-term. It takes time to do good things. You see, this cultural phenomenon of speed and growth at all costs is displayed in every startup, they all look the same….

—Jesper Kouthoofd, founder of Teenage Engineering

Measuring things isn’t always inherently bad; trying to optimize naïve proxy metrics almost always is. Cost-cutting is often inherently good; doing it in a way that degrades the customer experience (the ultimate generating function of profit) is almost always bad. The incentives to stray into short-sightedness are many. Somebody has to be empowered to say no.

Founders typically have a deep intuitive sense of the ineffable factors that make people love their brand, along with a well-honed sense of the company’s core value proposition and competitive advantage—the things that led it to flourish in the first place, which they by nature tend to foster and protect.

Founder-led operations often keep an edge ... because when there’s someone at the top who actually gives a damn about cars, watches, bags, software, or whatever the hell the company makes, it shows up in a million value judgments that can’t be quantified neatly on a spreadsheet.

—David Heinemeier Hansson (dhh) of 37signals

Indeed, the finest case studies in holding the line against the depredations of MBAification typically involve the stubborn will of a founder. To build a company for the very long term requires an enormous amount of discipline, vision, and patience—and some large measure of real control. Among the greats in this pantheon: Walt Disney, Steve Jobs, Yvon Chouinard (Patagonia), George Lucas, James Dyson, and the Dumas family (Hermès). While more than half of those enforced control against investors through private ownership, the others took great pains to insulate their companies from the pressures of Wall Street myopia. All of them were at one time or another dismissed with eye-rolling contempt by managerial-minded executives in their industries. Yet they built some of history’s greatest companies, which were not only creatively and culturally successful but also financially so.

Steve Jobs insisted that even hidden internal faces of Apple products be beautiful. One of Jobs’ heroes, Walt Disney, pursued a kind of otherworldly perfection at Disneyland to such an extent that I’m hard pressed to pick which examples to mention here. Perhaps the midcentury science fiction author (and friend of Walt) Ray Bradbury put it best. Describing a totally unnecessary fanciful architectural flourish added to the castle at Disneyland some time after it was built: “It cost $100,000 to build a spire you didn't need. The secret of Disney is doing things you don't need—and doing them well—and then you realize you needed them all along.” My favorite example is the Sisyphean polishing of every brass drinking fountain in Disneyland every single night. These things are hard to justify on paper, but Walt correctly observed: “people can feel perfection.”

Cost control is important in any business, but it is the job of the founder to understand and protect the extraneous essential. Creating a feeling of perfection in the eyes of your clients is a vastly under-appreciated moat.

This is why I believe, especially in the early decades of a company’s existence, founders must seek always to keep their brands free from the excessive influence of investors and their short-sighted MBA emissaries. One should work only with investors who think for the very long term—and plan to hold the company for just as long. Such investors are much more likely to defer to the brand-protective vision of a founder, because they’ll have more to lose by destroying what made the business successful merely for short-term wins. This requires some large measure of control, if you can manage it, but just as importantly an even greater degree of personal trust in the values and judgement of the investor.

The trouble for me at my crisis point with Norbauer & Co. was that not only was I not aware of any such investors but that, as far as I knew, the things I needed and cared about just seemed antithetical to the very premise of investing itself.

On one of those dark days in 2023 when I was wallowing in despair, ready to walk away from Norbauer & Co, I pointed all of this out to my husband Alan, who said something along the lines of “Wait a minute. Wasn’t Andrew Wilkinson one of your all-time favorite human beings? And didn’t I read recently that he runs some kind of investment thing now?”

Palm Pilot

Way back in 2007, I was in Chicago for the SEED conference, an event hosted by my longtime tech and business idols, David Heinemeier Hanson and Jason Fried of 37signals (another duo of unconventional founders who managed to maintain control over a very profitable long-term company).

I was stepping off the L train after the conference, returning to my hotel several miles away in a city where I knew no one, so I was startled to hear my name. I turned to find a lanky kid, whom I remember looking like an unlikely hybrid of awkward geek and hipster aesthete. He had recognized my name from the conference badge still dangling from my neck (Tiny’s empire, incidentally, now includes a conference badge company) and asked if I was the Ryan Norbauer who at the time wrote a guest column for 43folders—a now mostly forgotten website about productivity that was widely read in those days of a much smaller and nerdier Internet. I reported that, regrettably, I was indeed the personage in question. After a brief friendly chat, we swapped email addresses and went on our way. That skinny kid was Andrew Wilkinson (who would go on to co-found Tiny), and over the following weeks and years, we struck up a long correspondence. I still fondly remember his beguiling habit of vicious self-deprecation—and of calling businesspeople who took themselves too seriously “wieners.”

We were two insecure, upstart kids in our twenties, running two non-competing Web 2.0 agency businesses. Mine was doing back-end development, just as his was doing front-end—the now-famous Metalab that, among many other impressive projects, was pivotal in the design of Slack. (The full history of Metalab is excellently detailed in Andrew’s memoir, Never Enough: From Barista to Billionaire). This led to an obvious and easy bond—and a lot of commiseration.

Being fellow 37signals acolytes also made us feel like members of a furtive club of contrarian outsiders, a new guard of folks in the tech world who were questioning the orthodoxies of Silicon Valley, venture capital investing, and “enterprise software” with a kind of scorched-earth sarcastic rationalism. Andrew and I both have always been deeply skeptical of consensus narratives about how one is supposed to live a happy and successful life (a trait I find common among serial entrepreneurs). This line from Andrew’s memoir is one I could very easily have written about myself:

To this day, if anyone tells me what to do—no matter how reasonable—I will dig my heels in and resist, flashing back to being a kid.

In our teens, we had also both turned to computers and entrepreneurship as ways of answering and escaping uncomfortable aspects of our youth. We had come of age at that brief time when being part of internet culture made one feel special and weird—like humanity was on the cusp of something wonderful, and we were early to the party—in a way that I think shaped both our young identities. (That same spirit of the early web that is still a central feature of my own aesthetic life all these years later.) Another quote from his memoir:

My [tech] obsession was so severe that my unfortunate nickname in school was “Palm Pilot” because I walked around taking notes on a little black-and-white PalmPilot personal organizer, an early precursor to the iPhone. As you can imagine, the girls at school found this irresistible.

Not only did I excitedly carry one of these very same devices around at my own school but occasionally complemented it with a chirping Star Trek combadge on my shirt. We were clearly both cut from the same ridiculous cloth.

Knowing someone who shared so many of my values, goals, and neuroses simply made me feel less alone during a very stressful period of company-building, and our conversations became a kind of animating force for me in those days of drudgery and stress. Andrew was, as Alan would remind me nearly twenty years later, one of my favorite humans.

Mini-Buffett

Although I spoke with Andrew less often as the years passed, I was peripherally aware that he had become a professional investor, which—not knowing any of the details—is a fact I would of course normally have been disposed to meet with mild scorn. But knowing Andrew, I figured he must have found some charmingly idiosyncratic and benign take on it; I just never troubled to find out what it was.

It was only after my husband’s suggestion about reaching out to Tiny that I looked seriously into what Andrew had been doing with his fund these past years.

The first encouraging sign was the company’s unpretentious name. As Andrew explains:

We felt that all these private equity and investment firms had ridiculous, self-important (or borderline evil-sounding) names like BlackRock, Greywolf, and Maverick. We liked Tiny because it felt down to earth and friendly and, frankly, kind of ironic and funny.

Trying to learn as much as I could about how they operated, I started listening to Andrew’s many popular interviews on the My First Million podcast and elsewhere, where it became clear that he had indeed found his way into a characteristically nerdy and, to my mind, surprisingly inoffensive way of thinking about investing.

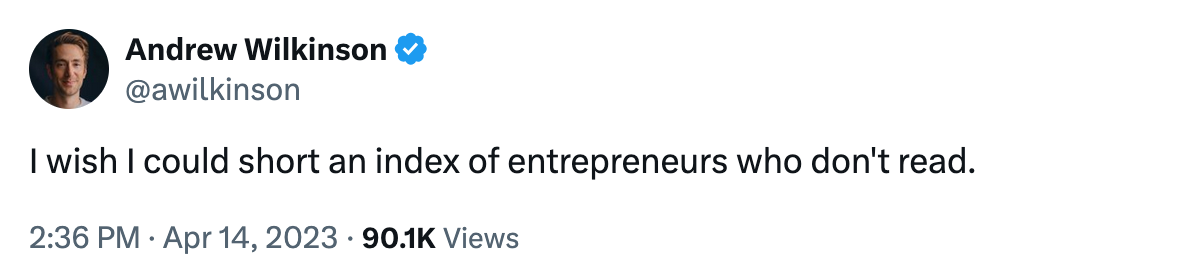

I was particularly pleased to observe that deep thinking, rationality, and reading all seemed to be explicitly baked into Tiny’s culture. Andrew, incidentally, has my all-time favorite Tweet on business or investing:

The many books I heard him mention in interviews sent me down a long reading journey that introduced me to the mental framework behind his particular weird corner of the investing world, which I found in itself to be a rewarding brainiac adventure. There was the douchey-sounding but actually quite excellent How to Get Rich by Felix Dennis (in which the affluent author undertakes to convince his reader that pursuing the goal mentioned in the title is a bad idea). There was Invention: A Life of Learning Through Failure, by James Dyson (of cyclonic vacuum fame), a magnificent portrait of a founder who doggedly pursued a quixotic creative vision in a way that no naively rational manager or investor would ever abide. There was The Outsiders: Eight Unconventional CEOs and Their Radically Rational Blueprint for Success, a masterpiece on business strategy and capital allocation, showing how managing companies in certain unorthodox ways actually leads to better results for shareholders. But surely the most instructive of these was The Snowball: Warren Buffett and the Business of Life, an incredibly dense and exhaustive biography of the man who inspired Andrew’s second professional life as an investor.

Tiny is often called “the Berkshire Hathaway of the Internet” due to their modeling their philosophy on that of Buffett and his business partner the late Charlie Munger. So earnest is their admiration that they run a little side business selling a $2,598 set of bronze busts of the duo. (Not quite as cool as Mr. McDuck, but not bad.)

The Berkshire approach focuses on acquiring profitable entities with a strong brand moat and loyal customer base, keeping out of the way of what originally made the company successful, supporting operations with ethical and experienced executives, and holding the purchased shares indefinitely. (Insanely, but tellingly, this is somehow considered a eccentric and contrarian take in the world of institutional investing—and an approach that, despite its prominent success, has rarely been copied.) Andrew and his co-founder at Tiny, Chris Sparling, have extended Buffett’s model to the world of technology and design—areas that they know well but in which Berkshire has historically been reluctant to operate. (It is outside their “circle of competence,” as Munger would have put it.)

Two really important and relevant recurring themes of The Snowball are Buffett’s very long time horizon when it comes to investing (“buy and hold forever”) and the paramount importance of reputation in business. Note that these are both explicit counterpoints to the things that I said I dislike most about the typical investor mentality (namely, short-termism and an indifference to brand erosion).

As Buffett famously once said in a briefing to employees, “Lose money for the firm, and I will be understanding. Lose a shred of reputation for the firm, and I will be ruthless.” There are countless other examples in his biography of an obsession with reputation. He stresses that, even when misbehavior in any one transaction could be financially advantageous, it is not worth the potentially catastrophic damage to one’s brand—personal or otherwise.

This has often accrued to very real business benefits for Berkshire. Buffett drafts up very short and simple (1-2 page) offer letters to potential acquisitions, predicated on good faith rather than legal constraints. Berkshire’s goal is, by cultivating a reputation for fair-dealing, integrity, and zero bullshit, to be a preferred buyer and thus to avoid getting into bidding wars. Founders proactively want to sell to Berkshire, because they want to see their good names endure and their companies flourish over the long haul, and they can trust Buffett to keep his promise to do just that.

My Tim Cook

In my study of both the Berkshire and Tiny approaches (to which, I must confess, I dedicated some months of reading and rumination) there was one other critical idea I encountered. Buffett rarely gets too deep into the operational weeds of the companies in which he invests. He buys firms that he believes have strong market positions and then stays largely out of the way, collecting dividends while waiting patiently for the next good opportunity to come along. “Lethargy bordering on sloth remains the cornerstone of our investment style,” as he wrote in a shareholder letter.

As a first order of business on an acquisition where the founders wish to change or diminish their role, Tiny seeks to bring in an executive. This was a lesson Andrew learned by chance before he even became aware of Buffett’s philosophy. He asked his old friend Mark to look after Metalab while he was away on vacation and discovered, upon his return, that things were actually operating more smoothly than when he was micro-managing the company before his departure. It’s a lesson I wish I had been forced to learn much earlier in my own entrepreneurial career, and it’s frankly one I still have trouble internalizing to this day.

In hindsight, it made all the sense in the world to do this, but at the time it was an anomalous thought that I almost felt guilty about. It’s a decision that many entrepreneurs fear making. I was embracing what I came to call Lazy Leadership: the idea that a CEO’s job is not to do all the work, but more importantly to design the machine and systems.

In all the stories of visionary founders I’ve read over the years, there was a subtle theme present for every one whom I admire: each had a trusted executive who handled the financial and operational side of things while the founder focused on the equally essential matters of brand and customer experience. Walt Disney had his brother Roy, who fronted for him with banks, struck legal deals, and made sure all of his little brother’s grand dreams were actually financially feasible. Gene Roddenberry notoriously had his rapacious attorney Leonard Maizlish strike the business deal with the studio that gave him ironclad creative control over Star Trek: The Next Generation (the only way a wonderfully crazy show like that could ever have been made) along with an usually strong financial stake in any resulting revenues. I once heard an interview with billionaire luxury shoe designer Christian Louboutin about how he rarely looks at financial statements and trusts his business partners to handle everything other than the creative work; he just thinks about shoes all day. George Lucas had a similar arrangement at Lucasfilm. Dyson has a CEO running things in Singapore so he can tinker around with wacky R&D projects in England. And, of course, Steve Jobs had Tim Cook.

I heard Andrew tell many stories of companies either that he had run or that Tiny had acquired where the founder was essentially holding the company back by not delegating to a trusted executive. Tiny’s strategy, immediately on buying a business (if not before), is typically to find someone who has run a similar company but at approximately double the size of the current business—the idea being that they’ll know from direct experience how to take the business to the next level. For example, when they bought Aeropress (and the founder wanted to step out of the picture), Tiny hired the former President of SodaStream to run it. That CEO massively grew the business in a few short years, leaving Andrew able to luxuriate in the results idly from afar. Something similar happened with Dribbble, where its founders had grown a huge base of happy users but weren't sure where to take the business next on their own. Under Tiny’s new CEO, the community saw explosive growth, while still allowing the founders to hang around and keep doing the bits they enjoyed.

I started to get excited imagining what it might look like for me to be off in my keyboard playground all day like Dyson or Louboutin—focusing only on making amazing product and building the brand. I would have been quite happy to get out of the way so that someone who actually knew what they were doing could keep an eye out for those cash incinerators, tax filings, bank nonsense, and all the little logistical minutiae that gobbled up my creative energy (and, for that matter, my will to carry on in the business at all).

I can’t stress enough how transformative this simple shift in thinking was to me. While I had often sought, here and there, to outsource simple tasks as cheaply as possible in the past (such as hiring a warehouse crew to put things in boxes), the thought had never occurred to me to find someone actually to run my company for me. I think I had also somehow implicitly felt a (stupidly) moralizing obligation to do all those things myself in order to be a worthy founder. But, of course, there is no virtue in soldiering on through something at which your skills are only middling at best, especially when you could be focusing instead on areas where you actually have some unique value to add.

Here is how Andrew puts it in his book:

…there is always somebody else who loves the job you hate. You might find accounting boring, for example, but I promise you there is somebody whose idea of a great night is eight hours of pivot tables in Excel. You might find coding to be the most laborious and painstaking job on Earth; someone out there can’t believe you’re going to pay them to write code. And you might hate running a company, which was someone’s dream job.

It’s basically the idea of comparative advantage from economics: a non-zero-sum game where all parties win by contributing what they do best. Presumably there was a spreadsheet jockey out there who needed someone like me to create the artistic product that generated numbers to populate his or her pivot tables. I realized I needed my Tim Cook.

And so I decided to approach my old buddy Palm Pilot to see if he might have any interest in partnering up with the world’s nerdiest luxury business to make exactly that happen.

Money that I didn’t need

The business world has many people playing zero sum games and a few playing positive sum games searching for each other in the crowd. —Naval Ravikant

Getting an offer from Tiny was, oddly, much easier than getting a quote from many manufacturers I’ve worked with. I simply gave them a little writeup on the history of my business (way shorter, in fact, than the one you’re currently reading) along with a login to our Shopify so they could check some basic financials. Tiny only ends up investing in far less than 1% of the opportunities that come across their desk, but apparently the analysts whom Andrew put on the task of evaluating Norbauer were compelled by what they found.

The offer was extremely short and simple, in classic Berkshire style. They would make an investment into the business that would leave me fully financially de-risked (even if the company went to zero), and they would bring in a talented executive to function as a kind of COO. (At some point we just took to calling this role “Norbauer’s Tim Cook.”) In exchange, they would get a 49% minority share in the business and a commensurate portion of any future profits.

Incidentally, if it were merely a matter of a share in future profits, I would readily have taken less than 51%, but I felt that retaining control was important to assure the keyboard community that I wasn’t ceding the business to the money people. This also gave me the power to ensure that no cost efficiencies would ever get in the way of the client experience: my Founder’s No.

Our shared long-term strategic vision was to launch the ready-to-type line I had been building for years, starting first with the Seneca, and in doing this, to give us a shot at building a great luxury brand that could endure for decades.

I knew it was a good idea to accept the offer when, on sharing the details with all my friends in the VC world, every single one of them told me I shouldn’t take it. Many suggested that I should get competing offers from private equity firms (not something I would ever in a million years consider). But some did raise one reasonable objection. The funny thing is that Norbauer has always been actually perfectly well capitalized. So, as they pointed out, I could actually in theory just have figured out how to hire an executive entirely on my own using cash in the bank.

But that sounded really hard, and I frankly just didn’t know how to do it. I’ve historically been awful at hiring and extracting the best performance out of employees—and especially letting people go when it’s obvious that things aren’t working out. (I’m simply too polite—another area where I could do to be a bit more like my desk-side mentor.) This failing of mine is costly and problematic enough when it’s a low-paying menial job, but with something as high-stakes as a well-paid executive there just seemed like so many things that could have gone wrong, and I didn’t trust myself to get it right on the first try. Tiny, by contrast, does this kind of strategic hiring all day long; it's their superpower, and their secret sauce.

Anti-goals

I likely could have negotiated for more money than Tiny offered, but I didn’t really care. I figured if these guys know what they’re doing, the company will do well and we’ll probably make some money eventually together. I was looking for long-term incentive alignment with smart people rather than a quick payday, and my goals were primarily subjective and psychological.

Andrew, borrowing from Munger, stresses the importance of anti-goals in business. Taleb calls this the via negativa: the fact that it’s often easier to arrive at what you want by eliminating bad things rather than adding new theoretically good ones. I’m a big via negativa kind of guy.

Here was my anti-goals list for a potential Tiny deal:

- Ever touching a spreadsheet The main thing I needed was someone to do the important business analysis for me, attending to the low-hanging fruit but without optimizing the client experience into the ground.

- Drowning in “little tasks” While productivity and hard work have (to a fault) never been scarce commodities for me, I’m really only effective when I can serially hyper-focus on things. The only things I’m any good for require me to go off into the wilderness, as it were, for weeks at a time so I can think clearly and deeply on problems. I needed to get the endless little administrative to-dos off my desk so I could actually effectively do that.

- Feeling alone This last is perhaps the most important. I was just sick of not having anyone to validate or sanity-check my strategic choices and plans—to encourage me in the things I was doing right, and to help me realize when I was putting my attention on the wrong things. As a solo entrepreneur I’ve always been prone to anxious freak-outs when little hiccups arise in a business, because I know if I’m not taking them seriously there is nobody else to do so. I had increasingly come to realize that facing problems like this entirely on my own simply feels bad. Maybe it’s a kind of weakness and I should be embarrassed, but in any case I had at least reached the level of maturity to acknowledge that, at this point in my life, I wanted something else.

Optionality

In addition to anti-goals, another really important thing for me is optionality. I reached out to Andrew to clarify some edge-case scenarios before agreeing to the deal, and he gave me the following (astonishing) assurances:

- If the business failed, no big deal. It happens, he said; we share the risk and just suck it up together and move on if so, no hard feelings.

- I could walk away whenever I wanted. I really am a contrarian bitch; it’s deep in my veins. I basically find it impossible to do something if I have to do it, and even if I can whack up the ginger under those circumstances the work becomes slow and painful. (At the very least, I have to be tricked into believing it was my idea.) Andrew told me early on that I wouldn’t be shackled to the business, and if I ever wanted to walk away they would just find someone to replace me. That’s not going to happen, but only because I know it could if I wanted it to.

- The big red FUCK OFF button on my desk Knowing how I bristle at being constrained, Andrew volunteered another point of optionality. He recounted the story of another company in which Tiny had made a majority (controlling) investment. The founder had stayed on running the business and Tiny occasionally made managerial recommendations. That founder eventually got annoyed, telling Tiny to fuck off and stop telling him what to do. And they actually did as instructed, trusting that he knew his company better than anyone. The founder sold the company for some healthy multiple just a few years later, creating a huge payday for Tiny. Andrew said he considered this a fantastic outcome and wouldn’t have done anything different. He offered this as an example that I could tell his team to get out of my hair at any time as well.

Yes

As we were nearing finalizing things, the Partner at Tiny who was putting the deal together reached out to me to make one last clarifying point. He said he just wanted to check in with me to make sure I didn’t have revenue growth expectations that were too high for the first few years.

Yes, you read that right; this was a potential investor who was checking with me, a creative founder, that I wasn’t going to expect them to MBA the shit out of my company right off the bat, because if so they weren’t sure they could deliver.

I happily signed on the dotted line.

Caleb and Year Zero

Do not seek a replica of yourself to delegate to, or to promote. Watch out for this, it is a common error with people setting out to build a company. You have strengths and you have weaknesses in your own character. It makes no sense to increase those strengths your organization already possesses and not address the weaknesses.

—Felix Dennis, How to Get Rich

The executive whom Tiny proposed to be my Tim Cook was Caleb Bernabe, who is now our Executive in Residence (a position he shares among a few portfolio companies that don’t yet require a full-time executive). He acts essentially as our COO, but his job description is basically doing all the things that I hate—a skillset at which he inexplicably but admirably excels.

Like me (and Andrew), Caleb is a fellow refugee from both startups and university education, a founder who sold his company and ended up where he is now through a series of accidents during a listless period of existential crisis—essentially as a solution to boredom.

When it comes to being a hipster aesthete, though, Caleb puts even Andrew to shame. He’s into 90s hip hop, vintage Porsches, and Leica cameras (film only, of course). Purely for fun, he runs a fashionable natural wine bar in Victoria, BC.

But my favorite fact about him is that, when he came to Utah to offer moral support at a conference talk I gave, he showed up in a streetwear hoodie and newly bleached-blond hair, looking like he had just rolled out of a Santa Monica skate park. Yet I knew that the very next day he was on his way to New York to negotiate on Tiny’s behalf in a high-stakes bidding war against one of the richest men on earth and an army of slick-haired suit-wearing MBA consultants. (He showed up in the hoodie.)

He’s exactly the sort of person I’d expect Andrew to pick as an analytical and operational wizard.

Caleb personally co-invested in Norbauer & Co. as part of the Tiny deal, following the general ethos of maximum skin-in-the-game incentive alignment. He makes sure the lights stay on, projects stay on track, bills get paid, papers filed, and that I never have to monitor things like cashflow or other accounting details. Whenever financial modeling is required, he dives into those pivot tables with abandon but otherwise just leaves me alone to make the keyboards nice—with some welcome cheerleading from the sidelines when required.

Caleb is without question one of the smartest and most competent people I’ve ever had the pleasure to work with. There is approximately zero chance I would ever have hired so well if I had opted to go it alone.

It’s part of a broader trend I’ve noted: everyone at Tiny is just so ridiculously smart, competent, and rational. One presumes that such people exist in the world, but I’ve rarely had occasion to interact with them in my professional life. It’s all the rarer to find so many all in one place, and seemingly happy no less. (I vividly remember my first video call with Aman, the Partner assigned to evaluate a potential deal with Norbauer. I saw a bunch of insanely obscure books on his shelf that I thought nobody on earth had ever read other than me, so we spent half the call excitedly geeking out about that, rather than troubling too much about any details of the deal.)

The best part of my collaboration with Caleb in this past year is that we are so consistently on the same page about strategy, cost/quality tradeoffs, and vision for the brand. Of course, I was very careful when weighing the deal (and Caleb as an executive) to ensure that this would be the case. But he quickly put me at ease on that front. To also demonstrate my point about the articulate intelligence of the people at Tiny, I might as well quote at length from his pitch email to me:

As a frequent participant in hobbies and interests centred around extreme devotion to detail and artistry, I resonate with your approach to building. What’s even more striking to me, however, is your philosophy around luxury and brand. My existential issue with fashion, cars, even art and dining to some extent, is the misplaced idea of status that many casual participants (conspicuous consumers) attach to items and experiences. I often lament the mass adoption of status symbols, and search intently for those with a legitimate devotion to craft. You called this approach an antidote to late stage capitalism, as opposed to a result of it. I love that.

I’ve long wondered what would result if I were able to apply my ability and passion for building businesses towards an opportunity that exists more in this realm, rather than that of spreadsheets and sales optimizations (as much as I genuinely love those things, too). Usually, I end up thinking that this seems like too big of an ask for the universe, having my cake and eating it too. I feel genuinely, however, that working with Norbauer may be an opportunity to do just that.

What more need I say.

I can also report that Tiny as a whole has been ridiculously respectful of my role as founder and guardian of the brand. Well into the partnership, I asked Aman for his perspective on a video script I was working on, and here is the beautiful message he wrote me:

I want to be careful about giving too much of my take. Norbauer is an extension of you. And I’d be careful of questioning your instinct too much especially when it comes to the less tangible things about the business. It could compromise authenticity. Ideally, people listening hear your voice.

Caleb also once pointed out that various folks at the fund have been very interested in and curious about Norbauer since the acquisition—enthusiastically following along with the more subjective accomplishments we’ve been accumulating in the past year—but nobody at the head office has ever quizzed him on how many keyboards we’ve sold yet. Everyone remains far more interested in the long-term prospects for the brand and just diligently doing what we need to make it happen.

Psychological effects

While my motive for seeking a deal with Tiny was fundamentally psychological (i.e., wanting to walk out the window a little less), there have been a number of other unexpected—but very welcome—changes in my emotional relationship to the business.

It turns out that completely financially de-risking for a founder is pretty transformative. Even though I had always been fully prepared to lose every dollar I had put into the business, I think some part of me always worried that if things went to zero and I couldn’t return our personal capital I’d be letting my family down, which probably made me overly cautious. Now that I’m playing with the house’s money, as it were, I have a kind of emotional distance that makes it easier to reason dispassionately about risks.

In fact, I would say that the emotional voltage around decision-making in general is much lower for me. When you’re a sole founder who is making all executive decisions, each one carries a massive emotional weight. It’s not just a question of the financial consequences, but for me at least it has often been intimately bound up with a sense of self-worth and identity. If anything goes wrong, there is nobody else to blame but me. Something about stepping back and becoming a partner with others in the business helps me think about the company more like an investor (the good kind), thinking about the business at a slightly higher level of abstraction. Together, we all just try to do our best and approach things rationally.

Interestingly, I’ve also noticed an increased cadence and cost-consciousness has coalesced in my daily engagement with the business. There is something about having other people whom I like and respect who have a reason to care that helps me feel motivated to pay attention to those things that actually serve the business. Before, when it was just me, I had nobody to harm other than myself—which somehow made it much easier for me to indolently inflict that harm.

Since the deal, the business has already been more profitable than it ever has. Or so I’m told. (Louboutin-style, I usually don’t even look at the financial reports Caleb sends.)

Production on the Seneca proceeded beautifully, as I had hoped, through 2024. And we sold out our private “Edition Zero” offering almost instantly. We were awarded two patents for head-turning advancements in keyboard tech, with others in the pipeline. I have my Tim Cook, and my anti-goals have been kept far at bay.

Things in Year 0 have played out exactly as Andrew puts it in his book:

I realized that [Tiny] appealed to founders who didn’t relish the idea of selling their beloved company to some private equity firm run by people who viewed their business as a spreadsheet and would chop it up for parts then flip it to the highest bidder. Founders like us. We could come in, give the founders a huge payday, and do our best to solve all of their problems. Problems we’d learned to solve the hard way. It didn’t mean they had to leave, either. We could offer deals where the founders stayed on and kept running the business, taking some chips off the table. Or, if a founder wanted, they could just advise the business and leave the day-to-day to us.

Year 1, and Straight on to the Retrofuture

Now it’s 2025 and I’m moving into my second year with Tiny’s help.

We just brought on a new member of our executive team to head up Client Experience, Taeha Kim, who is also now an incentive-aligned investor in the business. Taeha has long been the leading tastemaker and influencer in our industry and, as part of our deal, his half-million-subscriber YouTube channel came to Norbauer & Co. with him. There is probably no single person on this planet better poised to do this critical job for us, and I’m certain that this deal would never have happened without Tiny’s involvement (I would simply not have had the ambition or risk tolerance even to explore it.)

The Seneca is now a real thing in the physical world, and it has been generating enormous buzz, both within the keyboard world and beyond, as we moved towards our more public First Edition launch this week.

The product and brand are stronger than ever. I have an amazing crew to dream alongside me. We’re doing cool shit together and having a great time.

And not once have I even had to turn the key to open up the little protective acrylic cover over the big red FUCK OFF button on my desk. But it has brought me great comfort to know it was always there.

I used to think that building something great required carrying all the significant burdens on my own. That the price of creative freedom was solitude. And that those shards of glass were just a necessary part of the meal.

At least with respect to one rather exceptional investment firm, I was wrong.

I just had to find investors who think for the long term—and who respect the art of business at least as much as the business of business. People who could run the spreadsheets for me, but also see beyond them. And find them I did.

For the first time in my life as a founder, I’m not staring alone into an abyss.

I’m looking into The Future.

And I’m smiling like an idiot.